mardi 21 avril 2020

Le café Partout et la maison du Préposé aux ponts tournants

Le café Partout en face de la maison du Préposé aux ponts tournants de Troyes ( qui héberge le siège de l'association Sauvegarde et avenir de Troyes de nos jours).

Louis Partout, né à Radonvilliers, a épousé le 9 avril 1872 au Petit-Mesnil, Marie Darnet, demoiselle de magasin chez le marchand de Chaussures Edouard Colonval au 1 rue de l'Hôtel de ville.

Au recensement de la population de Troyes de 1872, ils apparaissent au 2, rue de l'Hôtel de ville, Louis Partout exerçant le métier de limonadier avec sa femme Marie et son frère Isidore Partout.

Les familles Partout et Darnet géreront le café Partout, qui apparait sur plusieurs cartes postales, pendant un demi-siècle, jusqu'au milieu des années 1920.

La rue de l'Hôtel de ville s'appelle désormais rue Georges Clémenceau. Le café Partout est devenu une pharmacie et le magasin de chaussures Colonval est un bureau de tabac, distributeur de journaux.

Louis Partout, born in Radonvilliers, married Marie Darnet, on the 9th April 1872 in the village Petit-Mesnil.

Marie Darnet was a seller in the shoe shop of M. Colonval 1, street Hôtel de Ville (City hall street).

Some months after, on the census 1872 for Troyes, Louis Partout was described as a 37 years old man, "limonadier" (lemon juice maker, in fact a café patron) with his wife Maria and his brother Isidore partout on the 2, rue Hôtel de Ville. For half a century, up to the middle of the years 1920,the two families Partout and Darnet, were the owners of a "Café Partout" which can be seen on several postcards.

The name of the street has changed, rue Georges Clémenceau. The café Partout is a drugstore, the shoe shop on the other side of the street, is a tobacconist's selling newspapers.

Libellés :

café Partout,

Préposé aux ponts tournants,

rue Clémenceau,

Troyes

Pays/territoire :

Rue Georges Clemenceau, 10000 Troyes, France

samedi 18 avril 2020

LIEFRA, colonie agricole socialiste Fontette(Aube) Paul Passy

https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/al/research/collections/elt_archive/halloffame/passy/life

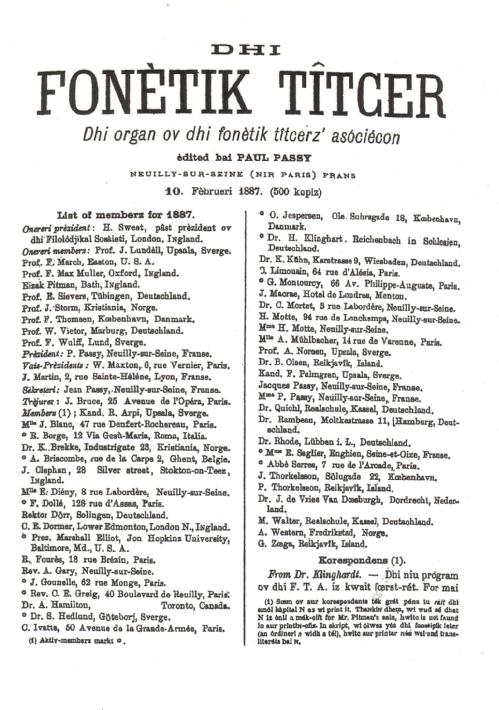

Paul Passy (1859–1940) was, like Otto Jespersen, in his early twenties when the Reform Movement ‘broke out’ in 1882, but, again like Jespersen, rapidly took on a leading role in extending its influence beyond Germany.

Passy was born into a ‘family of unusual distinction’ (Jones 1941: 30): his father, Frédéric Passy, was a noted economist and politician and first recipient of the Nobel Peace prize. (in 1901). Growing up in privileged surroundings, he received instruction at home and mastered three foreign languages (English, German and Italian) in childhood. He also developed an early interest in the observation and classification of speech sounds, even inventing his own rudimentary phonetic alphabet. Rather like Sweet, he initially found university uninspiring, though he eventually began to work on subjects more to his liking such as Sanskrit and Gothic Latin at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes. Graduating at the early age of nineteen he embarked on a career as a teacher of languages, contracting to teach in public institutions for ten years as an alternative to military service (he had recently become a committed Christian, and both evangelism and pacifism were to be life-long concerns). During this period he taught English and some German, mostly at the Ecoles normales of Courbevoie (1878–79) and Auteuil (for the following ten years).

Although (or perhaps because) he had not himself learned languages in a classroom, he soon came to the conclusion that the methods then in common use needed radical reform. From a practical perspective, he placed his hopes in the idea that language teaching could be carried out on a phonetic basis. From the first he laid stress on the proper articulation of foreign sounds, and soon introduced a system of noting them phonetically. He provided his students with texts in a phonetic transcription which he later admitted was crude and in some respects faulty; however, he found that he still got better results in terms of improving his pupils’ pronunciation. At this time he had still not studied the work of foreign phoneticians, and he followed the classical method in everything except his use of phonetic transcription. Indeed, he was not to change his basic methods of teaching until 1886, under the influence primarily of the German and Scandinavian reformers. However, he began to learn that phonetics was a whole science, not just a way of representing pronunciation (that is, a means of transcription). As he read more in the field, pushed by practical necessity and his own curiosity, he became more excited about the possible discoveries and applications to be made in the phonetic field. This period of self-instruction in phonetics seems to have lasted from 1879 to about 1885 (Galazzi 1992: 119). His inspirations were Sweet, Viëtor, Sievers, Storm, and Lundell, and he acknowledges having been guided in these difficult beginnings by a few friends such as Franke, Jespersen, and the Norwegian Western. Well-prepared by his own practical knowledge of several languages, he quite rapidly gained a certain mastery.

The August 1886 issue of The Phonetic Teacher contains the following announcement: ‘M. Passy has left Paris for Stockholm, whither he is commissioned by the Government, to report on the proceedings of the third philological Congress of the North’ (p. 3). Passy gave a brief account of his visit in the September 1886 issue, but the official report, published the following year, is much more detailed, and provides a riveting narrative of Reform activities prior to, at and immediately following this important Congress.

Passy, it should be remembered, was largely self-taught in phonetics, and claimed he had gained his first introduction to the study of foreign phoneticians via correspondence with Franke and Jespersen (it seems possible that, having read Franke’s 1884 pamphlet, Passy wrote to him and Franke put him in touch with Jespersen). In 1886, the correspondence with Jespersen was continued, and he was told about the forthcoming congress in Stockholm. It was therefore Passy himself who asked to be sent to Stockholm as an official representative of the French government: he had heard from Jespersen that there would be an attempt to promote Reform ideas similar to that at the previous year’s Giessen Congress in Germany, and he was eager to collaborate in this venture, aside from wishing to strengthen ties with the Scandinavian phoneticians, who already appeared to be among the most active reformers (see p. 12, foot).

This was not Passy’s first official visit; he had previously been sent on a mission to the USA to study the organisation of primary education in that country, and in 1885 he had been to Iceland to study its institutions and language and literature (pp. 1–2). His report on the Stockholm Congress (Passy 1887b) is not a complete one but is limited to the part of the proceedings which had motivated him to attend the Congress, hence the title of his report, Le Phonétisme au Congrès de Stockholm (‘Phonetism [a neologism of Passy’s invention?] at the Stockholm Congress’).

Although his main interest always remained the practical possibilities of phonetics for language teaching (in 1886 he founded the Phonetic Teachers’ Association which was later to become the International Phonetic Association (IPA): see below), he also realised that the phonetics of French was a rich field for further investigation. Indeed, he had already begun to issue textbooks in phonetic script for French schoolchildren learning to read (Premier livre de lecture, 1884) and for learners of French as a foreign language (Le français parlé. Morceaux choisis à l’usage des étrangers avec la prononciation figurée, 1886a), these in addition to his (1886b) Les éléments d’anglais parlé and an earlier textbook for the learning of English published in London.

The fruits of his studies in the phonetics of French over this period are contained in his (1887a) Les sons du français. In this work, all the qualities are apparent which made Passy such a persuasive and influential advocate for phonetics. As Jones (1941: 39) remarked, ‘He succeeded in establishing phonetics as a “living” science –– thus making it stand out sharply from various other academic subjects pursued in many modern universities’. Similarly, Collins and Mees (1998: 23–24) have defined his overall contribution as being related to his ‘ability to refine and simplify the complexity of phonetic and phonological information so as to produce an easily learnt framework which can be widely utilised’. They suggest that his Christian Socialist beliefs may have influenced his deliberate clarity of exposition, in which the elaborate theory of some of his sources is honed down to the essentials in a manner understandable to the non-specialist reader (including, of course, many teachers of languages). According to Collins and Mees (1998: 174), Passy 'considered phonetics to be in great measure a useful tool in language teaching –– a means by which human beings could establish better understanding with each other –– and, consequently, found much in the directness and empiricism of Bell, Ellis and Sweet to attract him. [. . .] The essentially practical linguistic approach of the British school had more appeal for Passy than the more objective, experimentally-based researches of his fellow countryman, Rousselot, or the "misplaced striving for physiological accuracy" which coloured the work of certain German phoneticians in the late nineteenth century (Kohler 1981)'. Thus, in Les sons du français, Passy does not overload the reader with excessive detail or transcriptional complication in the way Bell, Ellis and Sweet were at times prone to do.

This book was to be followed up by further academic work in the field of phonetics. In an article of 1888 in the newly-founded Phonetische Studien (Passy 1888) and in a doctoral thesis submitted three years later (published as Passy 1891a), he built on work by Bell and Sweet in investigating the articulation of vowel sounds, and this work was later to form an important inspiration for Daniel Jones’s Cardinal Vowel system (Collins and Mees 1998: 175). The second thesis he submitted to gain his Doctorat-ès-Lettres was a phonetic account of modern Icelandic (Passy 1891b).

Although these relatively academic studies increased his standing in the field of phonetics (and were later to gain him a university position), Passy’s chief interest was always in the applications of phonetics to teaching children to read, and to modern language teaching. In 1893 he published a further pedagogic work, his Elemente der gesprochenen Französisch, and, in 1897, a jointly compiled Dictionnaire phonétique de la langue française (Michaelis and Passy 1897), the first attempt at a pronouncing dictionary of any European language to make use of IPA symbols.

As Jones (1941: 37–38) remarks, when still a young man Passy had realised that his qualifications were such as to assure to him a brilliant academic career should he choose to devote all his energies to phonetic science. However, his interests were wider, and he decided only to devote to phonetics energies which he considered ‘necessary to discharge conscientiously his professional obligations and to earn his living in an honorable manner’. Like Sweet, then, Passy could have had a more distinguished ‘academic’ career, but he deliberately rejected university academic prestige in favour of other, more ‘practical’ activities.

Passy’s work was clearly significant internationally (see above), but it also played an important role in bringing about the developments in France which led to the official recognition and approval of ‘Méthode directe’ at the beginning of the twentieth century (Galazzi 1992: 117).

Apart from his intensive work on behalf of the Association phonétique, Passy both gave and organised private lessons in phonetics and French pronunciation at his home in Bourg-la-Reine, Neuilly-sur-Seine. These attracted many participants, with a large number of them coming from abroad (Daniel Jones was to be one such visitor, in the early years of the twentieth century). He was often invited to give lectures and courses in different universities, both in France and abroad. For him, teaching was a kind of mission, and he gladly devoted more time to it than to purely academic research. Even so, he became a university teacher, almost in spite of himself (‘presque malgré lui’, as Galazzi (1992: 123) puts it). In 1892 Bréal invited him to lecture at the Sorbonne on the contributions phonetics could make to language teaching, and in January 1894 a new Chair in General and Comparative Phonetics was created for him in Bréal’s department in the École des Hautes Études. By 1897 he had risen to become an assistant director (‘directeur adjoint’) of the School.

In 1896 he began to give the lectures and practical classes in phonetics at the Sorbonne whose significance Daniel Jones (1941: 33) was later to describe in the following terms: ‘It’s no exaggeration to say that the success which has attended practical phonetics all over the world is to be attributed largely to Passy’s precept and practice there’. The classes seem to have always been full, sometimes to overflowing. Incidentally, Passy was the first teacher at the Sorbonne to insist that women should be allowed to attend his classes, and a similar attitude later characterised the appointments his pupil Daniel Jones made in the Department of Phonetics, University College, London (Collins and Mees 1998: 256).

In 1897 the Société pour la propagation des langues étrangères en France (Society for the Promotion of Foreign Languages in France) launched an essay competition for the year 1898 on the theme ‘De la méthode directe dans l’enseignement des langues vivantes’ (On the direct method in modern language teaching). Passy contributed an essay with the same title which was published in pamphlet form the following year under the auspices of the IPA (Passy 1899).

In this essay, Passy is careful to distinguish his own suggested method at once from a purely natural method (his is based on and appeals to reason and from the work of Gouin, which seems to him to over-emphasize comprehension over production. He is also at pains to stress that in his conception the mother tongue does not need to be banished entirely from the classroom (thus distinguishing himself from Berlitz). The contributions of translation and grammar are given their due place. All in all, then, the essay presents a reasoned and balanced argument in favour of a ‘direct methodology’ (in Puren’s (1988) sense) which is well-attuned to the realities of school-based language teaching at an elementary level. Perhaps surprisingly, the essay was only awarded second prize in the competition for which it had entered, but its contents were to be diffused widely, via the IPA.

Passy was to remain in his position at the École des Hautes Études until his retirement in 1926, apart from four years from 1913 when he was dismissed on political grounds (as a result of his publicly opposing an extension in the period of compulsory military service). This is just one example of the many-sided nature of Passy’s career. Aside from his pacifist and Christian evangelical activities (the latter reflected in his editorship of the journal L’Espoir du monde), in the late 1890s he had become a committed socialist, and he promoted a variety of causes via lectures, meetings and various practical enterprises with the same zeal he had devoted to spelling reform and the establishment of the IPA. Indeed, despite his practical linguistic achievements, they only occupied a secondary place in his life, and his autobiography, Souvenirs d’un socialiste chrétien (Passy 1930–32), devotes relatively few pages to them. First and foremost he was a militant Christian Socialist, and when he retired from his academic post it was to found a cooperative agricultural community which he named Liéfra (Li = Liberté, é = égalité, fra = fraternité). There, with others, he attempted to put into practice his ideal of a life lived close to nature which would combine fundamental Christianity, socialism and language teaching and learning (Collins and Mees 1998: 23).

Notes

The above essay by Richard Smith (uploaded here in 2007, slightly

modified in 2018) is adapted from Introductions to different volumes in

Howatt and Smith 2002. Passy’s own (1930–32) autobiography, Souvenirs d’un socialiste chrétien,

is one source for the details of his career presented here; also, Anon.

2006, Collins and Mees 1998; Galazzi 1992; Jones 1941; and Passy 1887b.

Source for photos: Anon. 2006.

References

Collins, Beverley and Inger M. Mees. 1998. The Real Professor Higgins: The Life and Career of Daniel Jones. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Anon. 2006. 'Paul Passy, fondateur de «L’Espoir du Monde», militant du socialisme chrétien et de la phonétique'. L'Espoir du Monde no. 128 (October 2006). Online: http://www.frsc.ch/f/documents/SCEM128oct06.pdf

Galazzi, E. 1992. ‘1880–1914. Le combat des jeunes phonéticiens: Paul Passy’. Cahiers Ferdinand de Saussure 46: 115–29.

Howatt, A.P.R. and Richard C. Smith (eds.). 2002. Modern Language Teaching: The Reform Movement (five volumes). London: Routledge.

–––––– 1887a Les sons du français: leur formation, leur combinaison, leur représentation. Paris: Firmin-Didot.

–––––– 1887b. Le phonétisme au congrès philologique de Stockholm en 1886. Rapport présenté au Ministre de l’instruction publique. Paris: Delagrave & Hachette.

Collins, Beverley and Inger M. Mees. 1998. The Real Professor Higgins: The Life and Career of Daniel Jones. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Anon. 2006. 'Paul Passy, fondateur de «L’Espoir du Monde», militant du socialisme chrétien et de la phonétique'. L'Espoir du Monde no. 128 (October 2006). Online: http://www.frsc.ch/f/documents/SCEM128oct06.pdf

Galazzi, E. 1992. ‘1880–1914. Le combat des jeunes phonéticiens: Paul Passy’. Cahiers Ferdinand de Saussure 46: 115–29.

Howatt, A.P.R. and Richard C. Smith (eds.). 2002. Modern Language Teaching: The Reform Movement (five volumes). London: Routledge.

Jones, Daniel. 1941. ‘Paul Passy’ (Obituary). Le maître phonétique, July–Sept. 1941: 30–39.

Kohler, K. 1981. ‘Three trends in phonetics: the development of

phonetics as a discipline in Germany since the nineteenth-century’. In

Asher, R.E. and E.J.A. Henderson (eds), Towards a History of Phonetics: In Honour of David Abercrombie, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Michaelis, H. and P. Passy. 1897. Dictionnaire phonétique de la langue française. Hannover: Meyer.

Passy, Paul. 1884. Premier livre de lecture. Paris.

–––––– 1886a. Le français parlé. Morceaux choisis à l’usage des étrangers avec la prononciation figurée. Heilbronn: Henninger.

–––––– 1886b. Les éléments d’anglais parlé. Paris: Firmin-Didot.–––––– 1887a Les sons du français: leur formation, leur combinaison, leur représentation. Paris: Firmin-Didot.

–––––– 1887b. Le phonétisme au congrès philologique de Stockholm en 1886. Rapport présenté au Ministre de l’instruction publique. Paris: Delagrave & Hachette.

–––––– 1888. ‘Kurze Darstellung des französischen Lautsystems’ (in 3 parts). Phonetische Studien 1: 18–40; 115–30; 245–56.

–––––– 1891a. Etude sur les changements phonétiques et leurs caractères généraux. Paris: Firmin-Didot.

–––––– 1891b. De Nordica Lingua. Paris: Firmin-Didot.

–––––– 1899. ‘De la méthode directe dans l’enseignement des

langues vivantes’. Paris: Colin. [Published as a special supplement to Le maître phonétique, May 1899.]

–––––– 1930–32. Souvenirs d’un socialiste chrétien, 2 vols. [Vol. 1, 1930; Vol 2, 1932.] Issy-les-Moulineaux (Seine): Editions ‘Je sers’.

Puren, Christian. 1988. Histoire des méthodologies de l’enseignement des langues. Paris: Nathan-Clé International.

Libellés :

biography,

Fontette,

LIEFRA,

Paul Passy,

Saint-Usage

vendredi 17 avril 2020

DISCOURS ADRESSÉ AU ROI DE SUÈDE, par M. l’Abbé DE RADONVILLIERS,

DISCOURS

ADRESSÉ AU ROI DE SUÈDE,

Par M. l’Abbé DE RADONVILLIERS,

Chancelier de l’Académie Françoise, lorsque ce Prince y vint prendre séance le Jeudi 7 Mars 1771

SIRE,

L’HONNEUR que Votre Majesté fait en ce jour à l’Académie n’est pas-nouveau pour elle, mais il n’en est que plus flatteur. Déja elle avoit eu la gloire de voir dans ses assemblées, au siède même où nous vivons, deux Souverains étrangers ; & le Roi son protecteur a bien voulu y venir occuper la place qui lui appartient. Les compagnies savantes attirent donc les regards des Rois, & font comptées parmi les objets dignes de- leur curiosité. Pour remplir les vues de VOTRE MAJESTÉ, l’Académie doit lui rendre compte du but qu’elle se propose & des travaux qui l’occupent.

Son but est de perfectionner notre Langue ; mais comme il y a une liaison naturelle entre la manière de parler & la manière de penser, l’Académie espéroit, en épurant le langage, épurer le goût, & l’événement a justifié ses espérances.

Elle s’occupe à célébrer les talents, les succès, & même les efforts de ceux qui cultivent les Lettres ; mais son intention n’est pas de se borner à de vains éloges. Elle veut, en excitant une noble émulation, donner aux hommes illustres des successeurs & des rivaux.

Une partie de ses discours est consacrée à la gloire du Roi ; c’est un tribut de devoir, d’inclination, & de reconnaissance. Mais, il en faut convenir, l’affection naïve du peuple a été plus éloquente que l’art de nos Orateurs. Elle a tout dit dans un seul mot, en donnant au Roi le surnom de Bien-Aimé.

L’un de nos Confrères est chargé d’écrire histoire de son règne, & le séjour que VOTRE MAJESTÉ a fait en France lui fournira un trait des plus intéressants. Après avoir raconté ce que publiait d’avance la renommée, & ce qu’il a fallu ajouter à ses récits, quand on a eu le bonheur de vous approcher, il en viendra au funeste événement qui interrompt le cours de vos voyages. Là il attendrira ses lecteurs en décrivant votre entrevue avec le Roi ; & cette aimable confiance, si rare entre les Princes, avec laquelle vous avez pleuré dans ses bras ; & cette douce sensibilité, peut être encore plus rare, avec laquelle le Roi a essuyé vos pleurs & les a partagés.

Heureuses les Nations auxquelles le Ciel accorde des Princes d’un caractère humain & sensible ! Dans les Rois, l’humanité est la première des vertus. Il en est d’autres qui fervent à leur gloire, celle-là sert à notre bonheur.

SIRE, je m’arrête là. Eh ! que pourrais-je dire encore qui fût plus agréable à VOTRE MAJESTÉ ? Le présage de la félicité publique, est le compliment le plus doux à l’oreille des bons Rois.

Claude-François LYSARDE de RADONVILLIERS

(extrait du site de l'Académie française)

Le roi de Suède était

Gustave III, né en 1746, couronné le 12

février 1771, quelques semaines avant cette réception.

Francophile, adepte de la philosophie des lumière, il

abolit la torture et il fonde en 1786 l’Académie suédoise, dont il rédige en

partie le règlement avec des missions calquées sur celles de l’Académie

française.

Il est assassiné le 16

mars 1792, au cours d’un bal masqué à l’opéra royal de Stockholm.

En 1833, le compositeur

français Auber compose un opéra en hommage à ce roi de Suède « Gustave

III, ou le bal masqué ».

En 1859, Verdi compose

sur la même intrigue « Un ballo in maschera ( Un bal masqué) «

mercredi 15 avril 2020

Louis Ulbach, Le Propagateur et l'un de ses collaborateurs

La lecture de ce numéro de La cloche de Ferragus permet de trouver un indice pour découvrir l'identité de ce collaborateur de Louis Ulbach qui n'est pas décédé en Algérie comme l'ont cru et écrit certains.

Libellés :

La Cloche de Ferragus,

le coup d'état de Napoléon III,

Le Propagateur,

les transportés en Algérie,

Louis Ulbach,

rédacteur en chef

Pays/territoire :

10000 Troyes, France

mercredi 8 avril 2020

Hommage à Claude VACHEROT, Président de la Société de secours mutuel des bonnetiers en 1841

Hommage à Claude Vacherot,

Président de la Société de secours mutuels pour les

ouvriers bonnetiers

L’AUBE

Troyes, le 20 janvier 1841

Avant-hier mercredi 27 janvier, un cortège nombreux

traversait la ville de Troyes, conduisant à sa dernière demeure un modeste

ouvrier. Cet homme avait fondé une société de secours mutuels pour les ouvriers

bonnetiers malades ou infirmes. Arrivés au cimetière, les sociétaires se sont

groupés autour de la fosse, et trois discours ont été prononcés. Nous donnons à

nos lecteurs le seul que nous ayons pu nous procurer.

Messieurs,

La mort vient de

frapper la société des secours mutuels des bonnetiers de la ville de Troyes, en

lui enlevant son président.

Affligé de cette

perte, j’élèverai ma voix pour rappeler à nos souvenirs le mérite modeste et

les titres de l’homme qui emporte nos regrets. Cette larme que nous nous

empressons de donner à sa mémoire, est une dette de cœur envers un ami, envers

un frère.

Né comme nous, dans

cette humble classe d’hommes à qui le sort ‘a donné que leurs bras pour

subvenir à leurs besoins. Vacherot n’eut qu’un désir, celui d’être honnête

homme et habile ouvrier. Tous ses efforts se porteront vers ce noble but il eut la douce satisfaction d’y atteindre.

Sa vie fut sans reproche, comme il le souhaitait son habileté a fait de lui le

modèle des artisans de sa profession.

La plus importante

fabrique de Troyes, la maison Jeanson, où il travaillait, le considéra bientôt

comme son premier ouvrier ; elle se l’attacha, parce qu’elle sut ce qu’il

valait. Vacherot en fut reconnaissant ; il jura de n’en jamais sortir. En effet, depuis vingt-cinq

ans, Vacherot était l’âme de l’atelier. Parmi les phases pénibles que le

commerce de bonneterie a parcourues, il est resté attaché à sa profession

paramour. Les diminutions de salaire n’ont point abattu son courage ; il a

soutenu le nôtre par sa résignation et son activité exemplaires.

Au –dessus de sa position par le cœur Vacherot

aimait ses camarades. Il sentit que tous les ouvriers bonnetiers n’avaient pas

comme lui, l’habileté en partage ; il vit que la modicité des gains était

peu en rapport avec les besoins d’une famille nombreuse quelquefois, et que

l’affreuse misère menaçait plus d’un honnête ouvrier. Il conçut le noble projet

d’une société de secours mutuel, en dressa les statuts dont il communiqua le

plan à son patron, l’honorable M. Jeanson. M. Jeanson l’aida de ses sages

conseils.

Encouragé par cette

approbation, et toujours mû par le désir de soulager ses camarades Vacherot

forma une demande et soumit son projet à l’autorité. Cette idée fût goutée. M.

le ministre accorda, le 12 avril 1837, l’autorisation de constituer la société

dont nous avons l’honneur de faire partie.

Le vœu philanthropique

de Vacherot fut accompli. Nous devions alors un hommage à la sollicitude de

Vacherot. Le titre de président lui fut confié : ce devait être sa

récompense.

Vous savez, messieurs,

comment il remplit ses fonctions. Vous avez pu, dans nos séances, remarquer son

zèle et surtout ses scrupules pour l’esprit d’ordre et d’harmonie qui fait

notre ressource.

C’est donc à Vacherot

que nous sommes redevables des secours dont plusieurs d’entre nous ont déjà

ressenti les effets.

C’est à toi, honnête

et modeste Vacherot, que nous en vouons

toute notre reconnaissance. Aussi, nous te pleurons sincèrement comme tu nous

as aimés, et avant de te quitter, nous te jurons que ton nom, sera

éternellement dans nos cœurs !

Adieu !!!

Ce discours, prononcé par M. Drujon aîné, l’un des

sociétaires, a ému les assistants jusqu’aux larmes, et la foule s’est retirée

en silence.

Claude Vacherot, bonnetier, époux de Jeanne Pitois est

décédé à l’âge de 46 ans, le 26 janvier 1841 à Troyes. Fils de Jean Vacherot,

âgé de 80 ans, et de défunte Anne Thibaut

L'Annuaire de l'AUBE, publie un autre historique pour cette société de

secours mutuel des bonnetiers de la ville de Troyes fondée en 1814 par

Eugène JANSON.

En 1861, la direction de cette société semble être revenue entre les mains de la bourgeoisie locale.

Libellés :

Claude Vacherot,

Eugène Janson,

Journal de l'Aube,

ouvriers bonnetiers,

société de secours mutuels,

Troyes

Pays/territoire :

10000 Troyes, France

mercredi 1 avril 2020

Dictionnaire des mots nouveaux, 2ème édition par Richard de Radonvilliers

Enrichissement de la langue française, dictionnaire des mots nouveaux, par M.Richard de Radonvilliers.

Commentaire publié le 19 décembre 1845 dans le quotidien national Le Siècle

Au premier coup-d-œil, le dictionnaire de M. Richard

de Radonvilliers a l’air d’un dictionnaire des plus effrayants barbarismes que

la langue française puisse créer, en se jouant avec malignité dans ses combinaisons.

Il est certain , par exemple, que les mots : abymiser, pour ouvrir des abîmes ; anglaiser, pour imiter la forme anglaise ; dédeuiller, pour sortir de deuil ; délicier, pour rendre délicieuse ; déprobiser, pour perdre la probité ;

funester, pour rendre funeste ; incomposer, pour ne pas composer ;

protocoler, pour faire des protocoles ;

vigiliser, pour devenir vigilant, etc

j’en passe, et des meilleurs, il est certain que ces mots éveillent les

susceptibilité des oreilles les moins délicates, et que si nous les entendions

prononcer, nous nous croirions pour le moins en Belgique, où la langue

française se permet de singulières excentricités. Eh bien ! M. Radonvilliers

a eu la constance de colliger vingt et un mille mots de ce genre, appuyant

chaque mot sur des étymologies et sur les terminaisons habituelles à notre

langue.

Ce travail pour lequel il a fallu une grande

patience et des connaissances grammaticales très approfondies, mérite d’être

pris en considération. A coup sûr, et même cela est à désirer, tous les mots

accueillis par M. Radonvilliers ne deviendront pas français, car l’harmonie de

la langue serait plus d’une fois offensée, mais beaucoup entreront tôt ou tard

dans le Dictionnaire de l’Académie ; il n’y a rien de répugnant à admettre

provincialiser, rengourdir, vitaliser,

et d’autres mots pareils. La langue française s’est singulièrement enrichie

depuis un siècle ; elle a encore des conquêtes à faire, et M. Radonvilliers,

comme un autre Christophe Colomb, s’aventure sur des mers inconnues, à la

recherche de mots nouveaux. On peut dire que dès à présent il plante sur des

terres inexplorées le pavillon français.

Inscription à :

Commentaires (Atom)